Commission Proposes New EU Foreign Investment Control Regime

Foreign investment control is subject to intense legal and political discussions in Germany, Europe and the U.S. In line with the general trend of increased scrutiny over foreign investments (see our newsletter on the recent reform of foreign investment control in Germany dated July 2017), the European Commission on 13 September 2017 announced the proposal for a regulation establishing a framework for screening of foreign direct investments into the European Union (EU) (“draft regulation”). The draft regulation responds to reform considerations initially submitted by the Ministers for Economic Affairs of Germany, France and Italy to the Commission in February 2017. The reform is expected to come into force no earlier than 2019.

The draft regulation aims to strike the balance between protecting critical infrastructures, technology and know-how of the EU and its Member States and welcoming foreign investments as major source of economic growth throughout the EU. The Commission’s proposal provides for a multinational screening process of foreign investments involving the Commission (“screening”). Screening shall not replace national foreign investment control. The draft regulation does not offer a one-stop shop solution for foreign investors either. They still have to pass through foreign investment control proceedings in various Member States. Clearance, restriction or prohibition of foreign investments remains a matter of national administrative practice and primarily subject to national laws.

However, any views of the Member States and the Commission on the foreign investment based on the screening will have to be taken into account by the national authorities. Screening may thus have substantial political weight for the national decision-making process and could, if rigorously applied and followed by the national authorities, emerge as key control instrument for EU inbound investments from China and other securitysensitive third countries.

Main Concepts of the Draft Regulation

1. Notion of Foreign Direct Investments

The draft regulation covers foreign direct investments within the EU of any kind by a non-EU investor aiming to establish or maintain lasting and direct links with the EU target company (cf. Art. 2 no. 1). Screening shall not apply to passive investments which are focused on financial gain and do not entail active management or control of the investor (“portfolio investments”). Apart from that, unlike German foreign investment control EU screening does not require that the foreign investment reaches or exceeds a certain level of control, e.g., above a participation threshold.

2. Scope and Reach of Screening

Screening shall involve any procedure to, inter alia, assess, investigate, prohibit or unwind foreign direct investments (cf. Art. 2 no. 3). The final decision shall be made by the competent authority of the Member State in which the foreign investment is planned or has been completed (“Reviewing Authority”) in accordance with the applicable national foreign investment control laws. Neither the other Member States nor the Commission will be competent to prohibit or unwind investments as a consequence of their investigations under the draft regulation. They may only raise their concerns or issue non-binding opinions (cf. Art. 8 and 9).

Screening is a restriction to free movement of capital or freedom of establishment and shall therefore be strictly limited to grounds of public order or security (cf. Art. 3 no. 1, no. 2). The standard is taken from Art. 65 and Art. 52 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and cannot be undermined by a regulation. According to settled case-law of the European Court of Justice, acquisitions may only endanger public order or security if they affect fundamental interests of society. The draft regulation further substantiates the notion of public order or security and provides a non-exhaustive list of “potential effects” that may be considered during screening (cf. Art. 4), including critical infrastructures in specific sectors (e.g., in the energy or financial sector), critical technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence or space technology), the security of supply of critical inputs or access to sensitive information.

Screening may also take account of whether a foreign investor is state-owned or significantly state-funded. As this will in many instances apply to Chinese investors, the Commission sends a clear signal that investments by state-owned or state-funded investors are under increased scrutiny. As under the German foreign investment control regime, screening does not depend on whether the legal and economic system of the state or region in which the foreign investor has its business place welcomes foreign investment or not (no “reciprocity test”). Germany had proposed such a reciprocity test at EU level but the Commission, while stressing the importance of reciprocal trade and investments, does not intend to make reciprocity a condition of foreign investment in the EU.

3. Regular Screening and Screening in Union Interest

The draft regulation is based on the idea that foreign investment in one Member State may potentially affect security interests of other Member States. As a consequence, Member States which consider being affected by the foreign investment may provide comments to the Reviewing Authority (Art. 8 no. 2). Accordingly, the Commission may issue an opinion to the Reviewing Authority if the foreign investment affects public order or security of at least one Member State (Art. 8 no. 3). The Reviewing Authority shall give “due consideration” to the comments and opinions of Member States and Commission (Art. 8 no. 6).

In special circumstances, foreign investments into EU markets may have an impact on interests of the EU as a whole, namely if they potentially affect “projects or programmes of Union interest”, in particular undertakings which involve a substantial amount or share of EU funding or which qualify as critical infrastructure, technology or input within the meaning of EU legislation (Art. 9 no. 1, Art. 3 no. 3). The draft regulation provides for a non-exhaustive list of six projects or programmes of Union interest (mostly huge trans- European undertakings), see the Annex. In such cases, the Commission shall have greater influence than within the scope of regular screening: The Reviewing Authority shall take “utmost account” of the opinion of the Commission (Art. 9 no. 5). As with regular screening, however, the Commission shall not be allowed to issue a binding opinion or overrule the final decision of the Reviewing Authority.

4. Procedure and Timeline for Screening

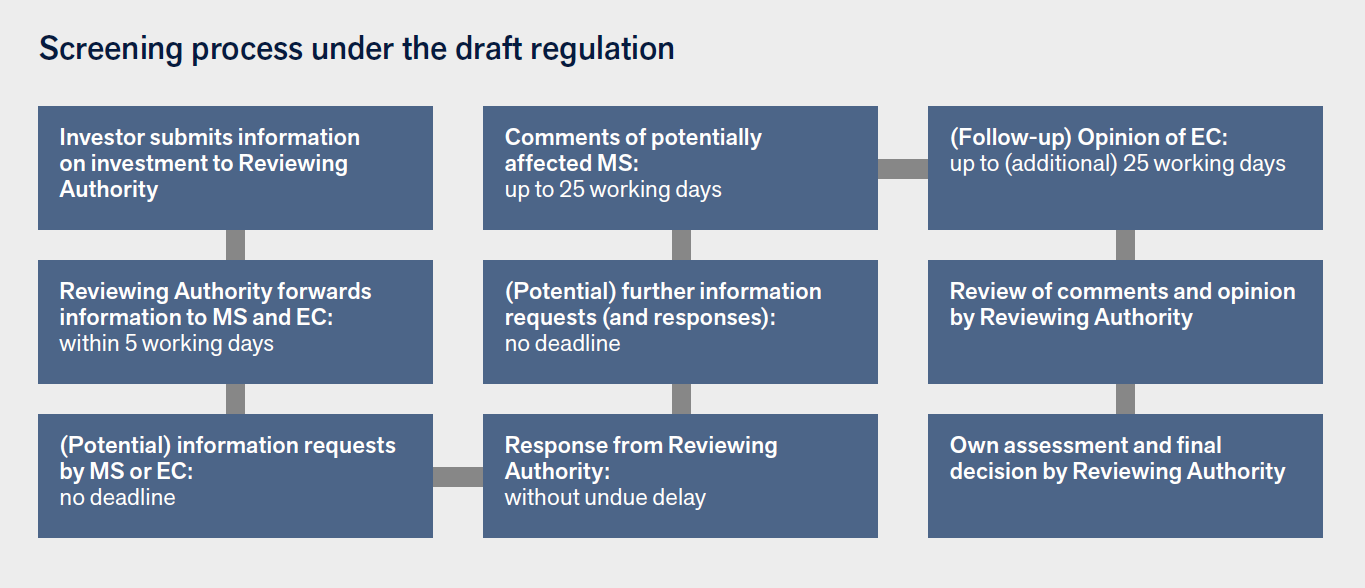

The draft regulation sets up a cooperation and information sharing mechanism to ensure that comments and opinions of potentially affected Member States and the Commission are based on complete and accurate facts (cf. Art. 8 to 10).

In particular, the Reviewing Authority shall inform the Commission and all Member States of any foreign direct investment “within 5 working days from the start of the screening”(Art. 8 no. 1). Thereafter, the Member States and the Commission may request from the Reviewing Authority any additional information necessary to provide their comments or opinions. On such basis, the Member States and the Commission shall have 25 working days to provide their comments and opinions. If the Commission follows up on comments of the Member States, it shall have another 25 working days for issuing its opinion.

Limited Effects of the Proposed Scheme

1. No Harmonization of National Laws and Regulations

The draft regulation does not harmonize the existing national foreign investment control regimes nor does it oblige Member States to implement a national foreign investment control regime if they do not have one (which is currently true for 16 of 28 Member States). The draft regulation rather seeks to provide a framework for Member States (including those which already have and those which plan on putting a national screening regime in place) according to which they may screen foreign direct investments (cf. Art. 3 no. 1).

2. No Central Responsibility on EU or Member States Level

Despite particular involvement of Member States and the Commission in national foreign investment control, the draft regulation leaves a high degree of autonomy to the Reviewing Authorities and accepts their role as final decision-maker. The draft regulation does not establish centralized foreign investment control proceedings which would allow investors to avoid national proceedings of the Member States (no “one-stop shop solution”). Also, the decision of one Reviewing Authority does not affect national foreign investment control by other Member States. In particular, there is no mutual recognition procedure in case the foreign investment has been cleared in one Member State.

3. No Revised or Extended Scope of Screening

First reactions to the draft regulation have controversially discussed whether the list of “potential effects” to be considered during screening (Art. 4, see under I.2. above) extends the standards of review applied by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie – “BMWi”) pursuant to the German Foreign Trade Ordinance (Außenwirtschaftsverordnung – “AWV”). In our view, the standards of review are consistent. Both regimes refer to the notion of public order or security as established by the TFEU and substantiated by the European Court of Justice. The list of potentially security-sensitive factors in Art. 4 of the draft regulation essentially corresponds to the approach of the AWV, even where the draft regulation refers to sectors or infrastructures which are not expressly covered by the AWV regime. By way of example, some of the “critical technologies” referred to in the draft regulation (“semiconductors” or “robotics”) are not mentioned in the AWV, however, have in the past been subject to particular scrutiny by the BMWi (see the Aixtron or Kuka transactions).

However, the draft regulation might influence the administrative practice of Reviewing Authorities (including the BMWi) by drawing their attention to foreign investments in the sectors and infrastructures listed in Art. 4 and to state-owned or state-funded investors. Further, Reviewing Authorities may now also consider public order and security interests of the EU Members States and the EU itself.

Potential Impact of the Draft Regulation on German Foreign Investment Control

1. Implications on AWV Periods and Deadlines

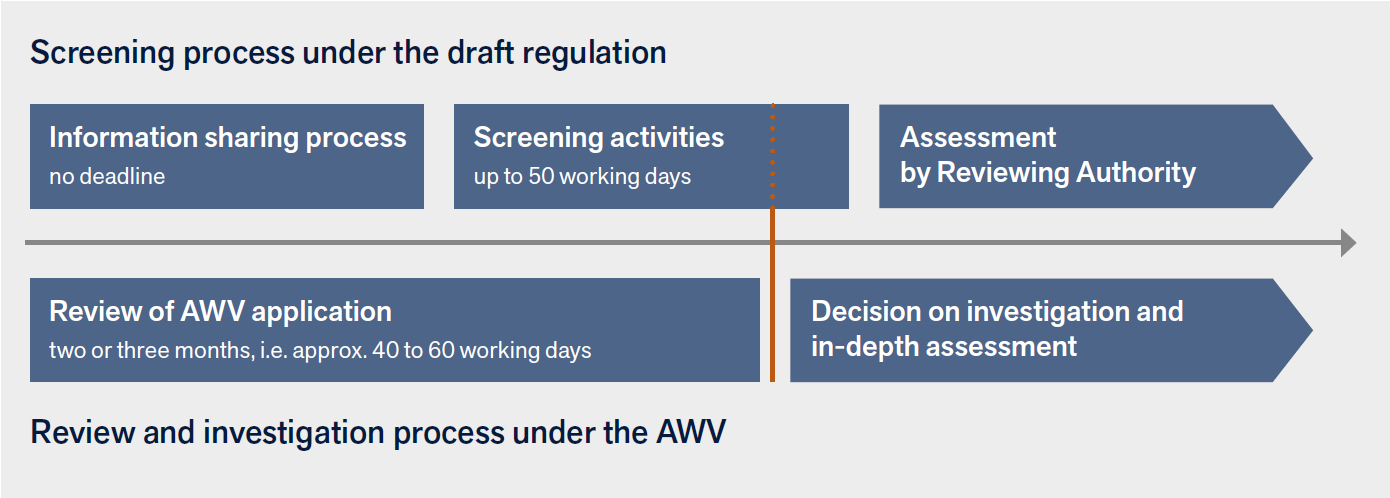

Screening as outlined by the draft regulation may take several months and therefore significantly delay a final decision in national foreign investment control proceedings.

The procedural framework for screening may conflict with the timeline of the investment review under the AWV. As a reminder, according to the AWV, upon receipt of the investor’s information, BMWi shall open investigation proceedings within three months (approx. 60 working days, defense and encryption sectors) and two months (approx. 40 working days, other sectors), respectively. Otherwise, clearance shall be deemed to have been granted. At this stage of the national review process (i.e., 40 or 60 working days after receipt of the investor’s information), however, the screening process by Member States and the Commission as provided for in the draft regulation may have not been completed yet, e.g., in case of repeated information requests by Member States or the Commission and/or if the Commission follows up on comments of the Member States. If the screening process exceeds the initial review period under the AWV, BMWi would need to open investigation proceedings merely because comments of Member States and/or the Commission are outstanding, irrespective of whether the BMWi itself sees a risk to (German) public order or security.

In practice, once the draft regime enters into force, it will be an ambitious task for BMWifactually to align the new screening process with the investigation timeline under the AWVregime

2. Implications on Content and Scope of AWV Applications

Under the draft regulation, if Member States or the Commission request additionalinformation on the foreign investment from the Reviewing Authority, the ReviewingAuthority is obliged to provide this information “without undue delay” (Art. 10 no. 1). Suchinformation requests may in particular refer to items listed in a (non-exhaustive) mannerin Art. 10 no. 2 of the draft regulation. The list includes the “value” and the “funding”of the foreign investment and, thus, goes beyond what the BMWi would usually requestfrom the parties of the transaction in accordance with the AWV. The BMWi will, however,only be able to provide the requested information without undue delay if and to the extentsuch information has been made available to the BMWi. As a consequence, once the draftscheme comes into force, BMWi may start requesting more information from investorsand targets in order to comply with the Member States’ or the Commission’s informationrequests.

3. Implications on the Official Language in AWV Proceedings

Based on general principles of German administrative law, all correspondence between theparties of a transaction and the BMWi within AWV proceedings shall be in German. TheBMWi regularly does not accept applications in the English language (there may be someexceptions for exhibits such as purchase agreements and annual accounts). In future, theneed for translations may further delay the process. The draft regulation does not addressthis issue. The Commission should develop a pragmatic translation and/or review processwhich can be handled by all Member States.

Key Takeaways for Foreign Investors

The current reform plans of the Commission do not substantially change established foreign investment control regimes at Member States level. The draft regulation rather seeks to enhance cooperation and exchange among Member States and with the Commission.

In terms of process, however, screening may have significant implications because the screening timelines of the draft regulation are partly incompatible with those under the AWV. There is a considerable risk that under the new regime completion of the AWV proceedings and, in most cases, closing of the transaction would in practice be further delayed.

The material impact of the draft regulation on foreign investments in Germany will presumably be limited. The review standard remains the same. However, the publication of the draft regulation is as strong signal by the Commission towards more thorough scrutiny of potentially security-sensitive EU inbound investments, in particular those by state-owned or state-funded investors. Such signal will likely result in a growing development and expansion of national foreign investment control regimes and a stricter administrative practice of Reviewing Authorities, which may now also address interests of the EU Member States and the EU itself. This might in particular apply to industry sectors and infrastructures addressed by the draft regulation which have previously not been the focus of the BMWi and other Reviewing Authorities (e.g., artificial intelligence). Foreign investments in those sectors and infrastructures are likely going to be under increased observation.

Generally, foreign investors should be aware that investments which used to be cleared by the BMWi and other Reviewing Authorities within a short timeframe may no longer be “straightforward” and become subject to time-consuming investigations. It remains to be seen whether such increased investigations will culminate in a first prohibition or growing restrictions of foreign investments in Germany and also the EU.